“Remove and abandon your false ideas about yourself, and there it is (the true Self) in all its glory. It is only your mind that prevents self-knowledge.”

—Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj

Intro to Self-Enquiry

There are a few ways to explain and practice self-enquiry; today we will go through just one of them. In India, they named this approach “Neti, Neti,” which, when translated into English, would be “Not this, Not that.”

Introduction to Neti Neti

This approach begins with a very logical premise: Everything that I can experience cannot be the same as who I am. Some people will take a moment and check if this is true for them; others will just take it for granted and continue to the next step. I recommend a healthy sense of doubt in all spiritual approaches, so please, take a moment and check if that premise is true for you.

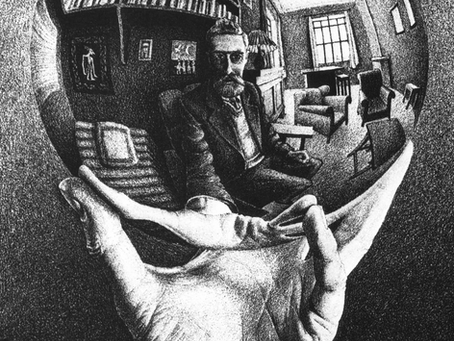

If you are still in doubt, let me elaborate on it. It is a basic subject and object differentiation that we have learned even since elementary school. The subject is the one who perceives, and the object is what is being perceived. By the same logic, if I (the subject) can experience something, by default, it means that the thing (the object) is not the same as I.

Many people live with an unconscious identification with the objects that they perceive. These objects can range from material ones such as a house, laptop, or a simple stone that has emotional value, to slightly subtler objects like relations with other people and animals, to the subtlest of all, such as thoughts, beliefs, ideas, and emotions.

By unconscious identification, I simply imply that we are not aware when we identify our sense of self with things or the objects of our experience. These unconscious identifications with things create an illusory self, known as the ego.

The Three Levels of Identification with Objects of Experience

The first one is relatively easy to understand because it is in relation to external objects. Meaning, anything that I can own, see, touch, and smell is not who I am. Yet, many people get their sense of self increased by their possessions or diminished by the lack of them. This is so because the nature of the ego mind is such that it thrives on comparisons, and so it will feel better about itself if it owns more things or more beautiful things than other people and vice versa.

Once it gets what it wants, it will fear losing them because that will diminish its sense of self. Simultaneously, it will focus on wanting the next thing, and this thirst for more is never-ending. The ego has this thirst for more because it always feels that it is lacking something, and often it will strive to fulfill this sense of lack by any means necessary.

Although some of these objects can make our lives easier, they will never bring lasting happiness and fulfillment if we keep identifying with what we have or don’t have.

So, the conclusion here is that we should learn to differentiate between what we need and what we want. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t go for the things we want. It means that it is mentally healthy to be aware that getting what we want will not fulfill that sense of lack.

We can also notice the unconscious ego-mind active in relation to other people. We may feel superior because we know someone famous or inferior when meeting someone important or powerful. The same form of the ego becomes activated when I think that we know more than someone else, or even something as simple as knowing something that the other person doesn’t know yet. You can notice the same patterns of the ego mind as before with physical objects—comparison and feeling better or more than others. The ego will probably become active when we speak in front of a larger audience than we are used to. Some people enjoy the attention, while others are afraid of it, but in both situations, we are relying on the opinion of others to form an opinion about ourselves, which is to identify with an idea about ourselves.

So the ego mind will form an idea of who I am, and as long as I believe in this idea, I will constantly re-evaluate myself by comparison with others, which is again a never-ending struggle, regardless of whether I find my idea of myself better or worse than the rest.

This brings us to the third and subtlest form of identification, which is the root cause of the other two. The real fun of this process begins when we ask ourselves if this unconscious identification is also true in relation to internal experiences—thoughts, emotions, ideas, and beliefs. This is the most important step because we never identify with the objects themselves but rather with our ideas and concept of those objects.

In our culture, we don’t recognize thoughts and emotions as objects at all, because they are not external. However, they are objects of our inner experience, our inner world. Like all other objects, they also have a form—a very subtle but powerful one. This process is much longer and more complex than the previous two, deserving an essay of its own, if not a whole book. However, I will provide a brief explanation.

I usually recommend people begin by observing their thoughts and emotions as they happen because it is through awareness of our thoughts and emotions that we recognize their impersonal nature. They are not yours; they appear to you. You are to observe them without trying to get rid of the unpleasant ones and indulge in the pleasant. This is known as equanimity.

It is relatively easy to become aware of negative emotions such as hatred, jealousy, anger, etc. However, some more subtle feelings are so common and persistent that they have become normal states of being for most people. I am talking about states such as impatience, nervousness, resentment, irritation, and dissatisfaction. Becoming aware of them as soon as they are triggered requires much more presence and alertness because they are easily justified by the ego mind.

The beautiful part of this practice is that it can be practiced at any time of the day, especially during daily routines like brushing your teeth, walking, waiting, or even while you read this. Although sitting still in a meditative position helps greatly, it is not necessary for this practice.

We should be very careful in this part of the process not to become sidetracked by interest in psychological analysis of some kind. We are not looking for something in our childhood that made us behave in some way; we are de-identifying from all the unconscious identifications so that we end up with the true Self as the subject of all experience.

The Recognition

Gravity is constantly pulling us down toward the planet, but we are unaware of it unless we point our attention to this experience. Similarly, the true Self is so constant in the background of all our experiences that we don’t notice it is always present. With this practice, it becomes clear that the true Self, which is synonymous with pure awareness, has been “veiled” by wrong ideas and beliefs of who I am. When the true Self is revealed, we call this spiritual awakening, which is nothing more than the recognition of our true Self and its nature. This recognition actually feels like re-cognition because it is often accompanied by a peculiar “I have known this before” kind of feeling.

Only then does one understand that the nature of the true Self is free of comparisons and the thirst for more; that is why the true Self is always content with itself. It was never created, so it can never be destroyed; thus, it is always at peace. When all the veils that cover the nature of our true Self are removed, the subject-object concept is transcended.